The practice involves shaping wood using manually operated tools with blades set within a rigid body. These tools, guided by hand, allow for the precise removal of shavings, resulting in smooth surfaces, accurate dimensions, and refined joinery. An example is flattening a board’s face to prepare it for further construction.

This method provides superior control over the material, leading to highly accurate and aesthetically pleasing results. It offers a tactile connection to the craft, promoting a deeper understanding of wood properties and grain direction. Historically, it was the primary means of preparing lumber and creating intricate details, shaping furniture and architectural elements for centuries.

The following sections will delve into the various types of tools used, techniques employed for optimal performance, methods for sharpening and maintaining the cutting edges, and considerations for wood selection and preparation.

Tips for Optimal Results

The following guidelines will contribute to improved performance and higher-quality outcomes when employing this shaping method.

Tip 1: Blade Sharpness is Paramount: A keen cutting edge is essential. Dull blades tear the wood fibers, leading to rough surfaces. Sharpening should be a regular part of the process, utilizing appropriate honing techniques and equipment.

Tip 2: Adjust Depth of Cut Incrementally: Begin with a shallow setting and gradually increase as needed. This prevents excessive force, reduces chatter, and promotes smoother, more consistent shavings.

Tip 3: Maintain Consistent Body Pressure: Even pressure across the tool’s body ensures a uniform cut depth. Avoid excessive force on the toe or heel, as this can lead to uneven surfaces.

Tip 4: Observe Grain Direction: Cutting with the grain prevents tear-out, resulting in a clean surface. Experiment with different angles to find the optimal approach for various wood species and grain patterns.

Tip 5: Employ Proper Stance and Body Mechanics: A stable stance and fluid movements are crucial for control and accuracy. Position oneself to maintain a straight line of sight and apply force effectively.

Tip 6: Wax the Sole Regularly: Applying wax to the sole of the tool reduces friction, allowing for smoother gliding and improved performance, especially on dense hardwoods.

Tip 7: Use a Fore Plane for Initial Flattening: A longer tool, such as a fore plane, is effective for removing larger amounts of material and establishing an initial flat surface before refining with shorter tools.

Adhering to these suggestions will improve both the efficiency and quality of the work, resulting in smoother surfaces, more accurate dimensions, and a greater understanding of the craft.

The subsequent section will cover advanced techniques and strategies for achieving specialized results.

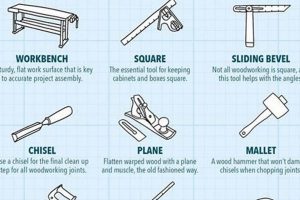

1. Tool Selection

The choice of implement is a critical determinant in the success of any woodworking project. Different tool types are engineered to perform specific tasks, and their selection directly affects efficiency, accuracy, and surface quality. For example, a jack plane is often employed for initial material removal and rough shaping, while a smoothing plane is reserved for achieving a refined surface. Utilizing a smoothing plane for material removal would be inefficient and potentially damage the tool. Conversely, using a jack plane for final finishing will not achieve the desired smoothness.

The size and configuration of the tool also play a significant role. A longer plane, like a jointer, excels at creating flat and straight edges on boards due to its extended sole, which bridges inconsistencies. A shorter block plane is advantageous for end-grain work because its compact size provides enhanced control. Furthermore, specialized tools such as rabbet planes and shoulder planes are designed for creating precise joinery, offering features that standard tools lack, such as blades that extend to the edge of the tool’s body. Therefore, the operator’s selection must align with the demands of the intended task.

In essence, the correct instrument serves as a force multiplier, enhancing precision and minimizing effort. A thoughtful approach to tool selection is not merely a preliminary step; it is a fundamental aspect that shapes the trajectory of the entire project. An inadequate tool will lead to increased work, lower-quality results, and potential frustration, while the appropriate choice streamlines the process, improves accuracy, and enhances the overall outcome.

2. Blade Sharpening

Blade sharpness constitutes a foundational element within the domain of woodworking. A dull blade fundamentally compromises the efficiency and quality of any hand-planing operation. Without a keen cutting edge, the process becomes an exercise in brute force rather than precision, leading to undesirable results.

- The Mechanics of Cutting

A sharp blade severs wood fibers cleanly. A dull blade, conversely, crushes and tears the fibers, leading to a ragged surface and increased effort. This tear-out is particularly problematic when working with figured wood or against the grain.

- Impact on Surface Quality

The quality of the finished surface is directly proportional to the sharpness of the blade. A finely honed edge leaves a smooth, lustrous surface, while a dull edge produces a rough and uneven finish, requiring extensive further work.

- Energy Expenditure and Control

A sharp blade requires less force to propel through the wood, allowing for greater control and reduced fatigue. With a dull blade, significantly more force is needed, diminishing control and increasing the risk of errors.

- Safety Considerations

A sharp tool is inherently safer than a dull one. A dull blade requires more force, increasing the likelihood of slippage and potential injury. A sharp blade engages the wood predictably, allowing the operator to maintain control and minimize risks.

These facets underscore the vital relationship between blade sharpness and woodworking. Consistent maintenance of blade edges through regular sharpening practices is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental prerequisite for achieving quality results and promoting safety and efficiency when employing this method.

3. Grain Direction

Grain direction fundamentally dictates the success or failure of shaping wood using bladed hand tools. The orientation of wood fibers relative to the direction of the cut determines whether the blade will slice cleanly or tear the wood. Cutting against the grain lifts and splinters the fibers, creating a rough, uneven surface known as tear-out. Conversely, planing with the grain allows the blade to shear the fibers smoothly, resulting in a polished surface. For example, attempting to flatten a highly figured maple board against the grain will inevitably result in extensive tear-out, requiring significant remedial work. Skilled manipulation involves identifying and adapting to changes in grain direction within a single workpiece.

Practical application of this understanding translates directly into the quality and efficiency of woodworking endeavors. When preparing a board for joinery, recognizing and compensating for grain direction is crucial for achieving tight, seamless joints. Mismatched grain orientation can weaken the joint or cause visual imperfections. For instance, when creating a dovetail joint, the angle of the grain on both pieces must be considered to ensure that the dovetails are cut with the grain, preventing chipping and ensuring a strong, aesthetically pleasing joint. Similarly, during surface preparation, the tool is frequently used at a slight angle to the grain, or even reversed in direction, to minimize tear-out and produce a smooth, uniform surface.

In summary, an awareness of grain direction is an indispensable component of effective technique. While the inherent variability of wood presents ongoing challenges, the ability to recognize and adapt to these variations is what separates expert craftsmanship from amateur attempts. Failure to respect grain direction not only compromises the quality of the final product but also increases the effort required and potentially damages the workpiece, underscoring the importance of this fundamental principle.

4. Surface Preparation

Surface preparation significantly impacts the efficacy and quality of woodworking practices. The condition of the wood prior to the use of bladed hand tools directly influences the outcome of the shaping process. Factors such as moisture content, existing surface imperfections, and overall flatness determine the ease and precision with which the tool can be used. Wood that is excessively wet or dry, for instance, may present difficulties during planing due to increased friction or potential for splitting. Similarly, pre-existing imperfections such as saw marks, knots, or unevenness must be addressed prior to the application of fine-tuning techniques. Failure to properly prepare the surface often results in increased effort, reduced accuracy, and a compromised final finish.

Practical examples underscore the critical nature of this preparation. Before creating intricate joinery, woodworkers frequently employ a series of planing operations to establish a perfectly flat and square reference surface. This reference plane ensures that subsequent cuts are accurate and that the resulting joint fits tightly and securely. Similarly, when preparing a surface for finishing, planing removes mill marks, scratches, and other blemishes, creating a pristine base for the application of stains, varnishes, or oils. This meticulous attention to surface preparation is crucial for achieving a professional-quality finish that highlights the natural beauty of the wood. Moreover, the choice of tool is often determined by the state of the surface. A scrub plane, for instance, may be used to remove large amounts of material from a rough or twisted board, while a smoothing plane is reserved for refining a relatively flat and even surface.

In summary, adequate surface preparation is an indispensable precursor to successful endeavors. It addresses inherent material imperfections, establishes dimensional accuracy, and optimizes the surface for subsequent finishing processes. While the specific techniques and tools used for surface preparation may vary depending on the project and the type of wood, the fundamental principle remains constant: a well-prepared surface is essential for achieving high-quality results.

5. Technique Refinement

Technique refinement represents the culmination of experience and focused practice within woodworking. It directly influences the precision, efficiency, and aesthetic quality achievable through this practice, transforming rudimentary skill into refined craftsmanship.

- Stance and Body Mechanics

Optimal stance and body mechanics are crucial for maintaining control and minimizing fatigue. A balanced stance, with weight distributed evenly, allows for consistent pressure and a straight cutting path. For example, bending at the waist rather than the back reduces strain and enhances stability. Proper technique also involves using the entire body, rather than just the arms, to power the tool, increasing efficiency and reducing the risk of repetitive strain injuries.

- Blade Angle and Overlap

Fine-tuning blade angle and overlap is essential for achieving a smooth surface and minimizing tear-out. Slightly skewing the plane relative to the wood grain can reduce the impact angle of the blade, resulting in a cleaner cut. Overlapping successive passes by approximately 50% ensures that no areas are missed and that the surface is uniformly planed. These subtle adjustments require careful observation and a deep understanding of how the tool interacts with the wood.

- Sharpening and Honing Cadence

Establishing a consistent sharpening and honing routine is fundamental for maintaining blade performance. The frequency with which a blade needs sharpening depends on the type of wood being worked and the duration of use. Regular honing, using progressively finer abrasives, maintains the keenness of the edge and extends the interval between sharpenings. Ignoring this cadence leads to a dull blade, increased effort, and a compromised surface finish.

- Reading and Responding to Wood Grain

Developing the ability to interpret wood grain patterns and adjust technique accordingly is a hallmark of refined ability. Complex grain requires careful assessment of the cutting direction to minimize tear-out. For example, reversing the planing direction or skewing the tool can mitigate the effects of opposing grain. This nuanced approach allows woodworkers to work with challenging materials and achieve exceptional results.

These interconnected aspects of technique refinement exemplify the sophisticated skill set necessary for achieving mastery. Through diligent practice and meticulous attention to detail, woodworkers can transform raw lumber into objects of both functional utility and artistic merit, showcasing the enduring value of precision and expertise in the art of woodworking.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the tools, techniques, and best practices associated with this type of woodworking.

Question 1: What constitutes a suitable initial investment for a beginner?

A foundational set should include a jack plane, a smoothing plane, and a block plane. Emphasis should be placed on quality rather than quantity. Refurbished vintage tools often offer excellent value. It is also recommended to include sharpening stones or sharpening system.

Question 2: How frequently should the blade be sharpened?

The sharpening frequency depends on the type of wood being worked and the amount of use. As a general guideline, the blade should be sharpened whenever it begins to feel dull or when the shavings become uneven or torn. Frequent honing extends the interval between full sharpening sessions.

Question 3: What wood types are best suited for this practice?

Softer woods, such as pine and poplar, are generally easier to plane initially. However, hardwoods like maple, cherry, and walnut can yield superior results with proper technique. Grain structure and figure should also be considered, as these factors can impact the ease of planing.

Question 4: Is dust collection necessary?

While not strictly essential, dust collection significantly improves the work environment. It reduces airborne particles, minimizing the risk of respiratory irritation and improving visibility. A shop vacuum or a dedicated dust collection system can be used to remove shavings as they are produced.

Question 5: What are common signs of improper technique?

Indicators of incorrect technique include excessive tear-out, chatter (vibration of the blade), uneven surfaces, and excessive effort required to push the tool. These issues often stem from a dull blade, incorrect blade setting, improper stance, or cutting against the grain.

Question 6: How is tear-out prevented?

Preventative measures include ensuring the blade is exceptionally sharp, cutting with the grain whenever possible, adjusting the depth of cut to a shallow setting, and using a backer board when planing end grain. Skewing the plane at a slight angle can also reduce the risk of tear-out.

These answers provide a basic understanding of frequently encountered challenges. Further research and practical experience are essential for developing proficiency.

The next section will explore advanced applications.

Conclusion

This exposition has detailed aspects of hand plane woodworking, encompassing tool selection, blade maintenance, grain consideration, surface preparation, and technique refinement. Each element constitutes a critical factor influencing the quality and precision attainable through this process. A thorough understanding of these principles facilitates superior outcomes.

Continued dedication to honing skills and expanding knowledge remains essential for mastering hand plane woodworking. The principles outlined provide a foundation for ongoing exploration and application. Pursuing this craft with diligence and precision yields results marked by both functional utility and enduring aesthetic value.